What Us Senator Wants To Change Our National Anthem

The earliest surviving sheet music of "The Star-Spangled Banner", from 1814 | |

| National anthem of the United States | |

| Lyrics | Francis Scott Key, 1814 |

|---|---|

| Music | John Stafford Smith, c. 1773 |

| Adopted | March 3, 1931 (1931-03-03) [1] |

| Audio sample | |

| "The Star-Spangled Banner" (choral with band accompaniment, 1 stanza)

| |

"The Star-Spangled Imprint" is the national anthem of the United states. The lyrics come up from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry",[2] a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-erstwhile lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry by British ships of the Royal Navy in Baltimore Harbor during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. Key was inspired by the large U.S. flag, with xv stars and fifteen stripes, known as the Star-Spangled Banner, flight triumphantly above the fort during the U.S. victory.

The poem was set to the tune of a popular British song written past John Stafford Smith for the Anacreontic Order, a men's social lodge in London. "To Anacreon in Heaven" (or "The Anacreontic Song"), with diverse lyrics, was already popular in the U.s.a.. This setting, renamed "The Star-Spangled Imprint", soon became a well-known U.S. patriotic vocal. With a range of 19 semitones, information technology is known for being very difficult to sing. Although the poem has iv stanzas, only the commencement is ordinarily sung today.

"The Star-Spangled Banner" was recognized for official utilise by the The states Navy in 1889, and past U.S. president Woodrow Wilson in 1916, and was made the national anthem by a congressional resolution on March 3, 1931 (46 Stat. 1508, codified at 36 U.s.a.C. § 301), which was signed past President Herbert Hoover.

Before 1931, other songs served as the hymns of U.Due south. officialdom. "Hail, Columbia" served this purpose at official functions for most of the 19th century. "My Country, 'Tis of Thee", whose melody is identical to "God Relieve the Queen", the United Kingdom's national anthem,[three] besides served as a de facto national anthem.[4] Following the War of 1812 and subsequent U.S. wars, other songs emerged to compete for popularity at public events, amid them "America the Cute", which itself was being considered before 1931 as a candidate to become the national anthem of the United States.[5]

Early history

Francis Scott Key's lyrics

On September 3, 1814, following the Burning of Washington and the Raid on Alexandria, Francis Scott Key and John Stuart Skinner set sail from Baltimore aboard the transport HMSMinden, a cartel ship flying a flag of truce on a mission approved past President James Madison. Their objective was to secure an exchange of prisoners, one of whom was William Beanes, the elderly and popular town physician of Upper Marlboro and a friend of Central who had been captured in his home. Beanes was accused of aiding the arrest of British soldiers. Fundamental and Skinner boarded the British flagship HMSTonnant on September 7 and spoke with Major General Robert Ross and Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane over dinner while the two officers discussed war plans. At first, Ross and Cochrane refused to release Beanes but relented after Central and Skinner showed them letters written by wounded British prisoners praising Beanes and other Americans for their kind treatment.[ citation needed ]

Because Primal and Skinner had heard details of the plans for the assail on Baltimore, they were held captive until later the battle, start aboard HMSSurprise and later on back on HMS Minden. Later the bombardment, certain British gunboats attempted to slip past the fort and effect a landing in a cove to the west of it, but they were turned away past burn from nearby Fort Covington, the city'south terminal line of defense.[ citation needed ]

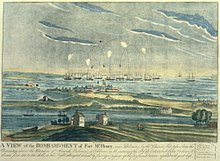

An artist's rendering of the battle at Fort McHenry

During the rainy night, Cardinal had witnessed the battery and observed that the fort's smaller "storm flag" continued to fly, but once the shell and Congreve rocket[6] barrage had stopped, he would not know how the battle had turned out until dawn. On the morning time of September 14, the storm flag had been lowered and the larger flag had been raised.[ citation needed ]

During the bombardment, HMSTerror and HMS Falling star provided some of the "bombs bursting in air".[ citation needed ]

Primal was inspired by the U.S. victory and the sight of the large U.S. flag flying triumphantly above the fort. This flag, with xv stars and xv stripes, had been made past Mary Young Pickersgill together with other workers in her home on Baltimore's Pratt Street. The flag later came to be known every bit the Star-Spangled Banner, and is today on display in the National Museum of American History, a treasure of the Smithsonian Institution. Information technology was restored in 1914 by Amelia Fowler, and again in 1998 equally function of an ongoing conservation program.[ citation needed ]

Aboard the ship the next day, Cardinal wrote a verse form on the back of a letter he had kept in his pocket. At twilight on September 16, he and Skinner were released in Baltimore. He completed the poem at the Indian Queen Hotel, where he was staying, and titled it "Defense of Fort K'Henry". It was commencement published nationally in The Analectic Magazine.[7] [viii]

Much of the thought of the poem, including the flag imagery and some of the wording, is derived from an earlier song by Central, also set to the tune of "The Anacreontic Song". The vocal, known as "When the Warrior Returns",[9] was written in honor of Stephen Decatur and Charles Stewart on their return from the First Barbary War.[ten]

Absent elaboration past Francis Scott Key prior to his decease in 1843, some have speculated more recently about the pregnant of phrases or verses, particularly the phrase "the hireling and slave" from the third stanza. According to British historian Robin Blackburn, the phrase allude to the thousands of ex-slaves in the British ranks organized as the Corps of Colonial Marines, who had been liberated by the British and demanded to be placed in the battle line "where they might await to run across their former masters."[11] Marking Clague, a professor of musicology at the University of Michigan, argues that the "middle two verses of Central'due south lyric vilify the British enemy in the War of 1812" and "in no way glorifies or celebrates slavery."[12] Clague writes that "For Key ... the British mercenaries were scoundrels and the Colonial Marines were traitors who threatened to spark a national coup."[12] This harshly anti-British nature of Verse three led to its omission in canvas music in World War I, when the British and the U.S. were allies.[12] Responding to the assertion of writer Jon Schwarz of The Intercept that the song is a "commemoration of slavery",[13] Clague argues that the American forces at the battle consisted of a mixed group of White Americans and African Americans, and that "the term "freemen," whose heroism is celebrated in the 4th stanza, would have encompassed both."[14]

Others suggest that "Fundamental may have intended the phrase as a reference to the Royal Navy'southward practice of impressment which had been a major factor in the outbreak of the state of war, or as a semi-metaphorical slap at the British invading force every bit a whole (which included a large number of mercenaries)."[15]

John Stafford Smith'southward music

Fundamental gave the poem to his brother-in-law Joseph H. Nicholson who saw that the words fit the popular melody "The Anacreontic Song", by English composer John Stafford Smith. This was the official vocal of the Anacreontic Lodge, an 18th-century gentlemen's order of amateur musicians in London. Nicholson took the poem to a printer in Baltimore, who anonymously made the first known broadside press on September 17; of these, two known copies survive.[ citation needed ]

On September 20, both the Baltimore Patriot and The American printed the vocal, with the note "Melody: Anacreon in Heaven". The song apace became popular, with seventeen newspapers from Georgia to New Hampshire press it. Soon after, Thomas Carr of the Carr Music Store in Baltimore published the words and music together nether the title "The Star Spangled Banner", although it was originally called "Defense of Fort Thou'Henry". Thomas Carr'due south organisation introduced the raised fourth which became the standard departure from "The Anacreontic Vocal".[16] The song's popularity increased and its first public functioning took place in October when Baltimore actor Ferdinand Durang sang it at Captain McCauley's tavern. Washington Irving, so editor of the Analectic Magazine in Philadelphia, reprinted the song in November 1814.[ commendation needed ]

By the early 20th century, there were various versions of the vocal in pop employ. Seeking a singular, standard version, President Woodrow Wilson tasked the U.S. Agency of Education with providing that official version. In response, the Bureau enlisted the assist of five musicians to hold upon an organization. Those musicians were Walter Damrosch, Will Earhart, Arnold J. Gantvoort, Oscar Sonneck and John Philip Sousa. The standardized version that was voted upon by these five musicians premiered at Carnegie Hall on Dec 5, 1917, in a program that included Edward Elgar'southward Carillon and Gabriel Pierné'south The Children's Cause. The concert was put on by the Oratorio Gild of New York and conducted by Walter Damrosch.[17] An official handwritten version of the terminal votes of these five men has been plant and shows all v men's votes tallied, measure past measure.[18]

National anthem

I of two surviving copies of the 1814 broadside printing of the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem that later became the lyrics of "The Star-Spangled Banner", the national anthem of the United States.

The song gained popularity throughout the 19th century and bands played information technology during public events, such every bit Independence Day celebrations.

A plaque displayed at Fort Meade, South Dakota, claims that the idea of making "The Star Spangled Banner" the national anthem began on their parade basis in 1892. Colonel Caleb Carlton, postal service commander, established the tradition that the song be played "at retreat and at the close of parades and concerts." Carlton explained the custom to Governor Sheldon of S Dakota who "promised me that he would try to take the custom established amidst the state militia." Carlton wrote that after a similar discussion, Secretary of War Daniel Southward. Lamont issued an guild that it "be played at every Army post every evening at retreat."[nineteen]

In 1899, the U.S. Navy officially adopted "The Star-Spangled Banner".[xx] In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson ordered that "The Star-Spangled Imprint" be played at war machine[20] and other advisable occasions. The playing of the song ii years later during the seventh-inning stretch of Game Ane of the 1918 World Series, and thereafter during each game of the series is frequently cited as the commencement instance that the anthem was played at a baseball game game,[21] though evidence shows that the "Star-Spangled Banner" was performed as early as 1897 at opening day ceremonies in Philadelphia and and so more regularly at the Polo Grounds in New York City beginning in 1898. In any case, the tradition of performing the national anthem before every baseball game began in World State of war II.[22]

On April 10, 1918, John Charles Linthicum, U.S. congressman from Maryland, introduced a bill to officially recognize "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the national canticle.[23] The bill did not pass.[23] On April 15, 1929, Linthicum introduced the bill again, his sixth fourth dimension doing then.[23] On November 3, 1929, Robert Ripley drew a console in his syndicated cartoon, Ripley'south Believe it or Non!, saying "Believe It or Not, America has no national anthem".[24]

In 1930, Veterans of Foreign Wars started a petition for the United States to officially recognize "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the national anthem.[25] Five million people signed the petition.[25] The petition was presented to the Us House Committee on the Judiciary on Jan 31, 1930.[26] On the aforementioned twenty-four hours, Elsie Jorss-Reilley and Grace Evelyn Boudlin sang the song to the committee to refute the perception that it was besides loftier pitched for a typical person to sing.[27] The committee voted in favor of sending the bill to the Business firm floor for a vote.[28] The House of Representatives passed the bill later that year.[29] The Senate passed the bill on March iii, 1931.[29] President Herbert Hoover signed the bill on March iv, 1931, officially adopting "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the national anthem of the United States of America.[1] As currently codified, the Us Lawmaking states that "[t]he composition consisting of the words and music known as the Star-Spangled Banner is the national anthem."[30] Although all four stanzas of the poem officially compose the National Canticle, just the beginning stanza is generally sung, the other three being much lesser known.[ citation needed ]

In the fourth poesy, Fundamental's 1814 published version of the poem is written as, "And this be our motto-"In God is our trust!""[eight] In 1956 when 'In God We Trust' was nether consideration to be adopted equally the national motto of the U.s.a. by the US Congress, the words of the fourth verse of The Star Spangled Imprint were brought up in arguments supporting adoption of the motto.[31]

Modern history

Performances

Crowd performing the U.S. national canticle before a baseball game game at Coors Field

The song is notoriously hard for nonprofessionals to sing considering of its wide range – a twelfth. Humorist Richard Armour referred to the song'due south difficulty in his volume Information technology All Started With Columbus:

In an attempt to take Baltimore, the British attacked Fort McHenry, which protected the harbor. Bombs were soon bursting in air, rockets were glaring, and all in all it was a moment of swell historical interest. During the bombardment, a immature lawyer named Francis Off Key [sic] wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner", and when, past the dawn's early light, the British heard it sung, they fled in terror.[32]

Professional and apprentice singers accept been known to forget the words, which is one reason the song is sometimes pre-recorded and lip-synced. Pop vocalizer Christina Aguilera performed wrong lyrics to the song prior to Super Basin XLV, replacing the song's quaternary line, "o'er the ramparts nosotros watched were so gallantly streaming", with an alteration of the second line, "what so proudly we watched at the twilight'southward last gleaming".[33] Other times the issue is avoided past having the performer(due south) play the anthem instrumentally instead of singing it. The pre-recording of the anthem has get standard practice at some ballparks, such as Boston's Fenway Park, according to the SABR publication The Fenway Project.[34]

"The Star-Spangled Banner" has been performed regularly at the beginning of NFL games since the end of WWII by order of NFL commissioner Elmer Layden.[35] The song has also been intermittently performed at baseball games since after WWI. The National Hockey League and Major League Soccer both require venues in both the U.S. and Canada to perform both the Canadian and U.Due south. national anthems at games that involve teams from both countries (with the "away" anthem beingness performed first).[36] [ better source needed ] It is also usual for both U.S. and Canadian anthems (done in the aforementioned way every bit the NHL and MLS) to be played at Major League Baseball game and National Basketball Association games involving the Toronto Blueish Jays and the Toronto Raptors (respectively), the simply Canadian teams in those two major U.S. sports leagues, and in All Star Games on the MLB, NBA, and NHL. The Buffalo Sabres of the National Hockey League, which play in a city on the Canada–US border and take a substantial Canadian fan base, play both anthems before all home games regardless of where the visiting team is based.[37]

Two especially unusual performances of the song took place in the immediate aftermath of the U.s.a. September 11 attacks. On September 12, 2001, Elizabeth II, the Queen of the United Kingdom, broke with tradition and allowed the Ring of the Coldstream Guards to perform the anthem at Buckingham Palace, London, at the formalism Changing of the Baby-sit, as a gesture of support for Britain's ally.[38] The post-obit day at a St. Paul's Cathedral memorial service, the Queen joined in the singing of the anthem, an unprecedented occurrence.[39]

During the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, the anthem was sung by protesters demonstrating outside the U.South. consulate-general in an appeal to the U.S. government to aid them with their cause.[40] [41] [42]

200th anniversary celebrations

The 200th anniversary of the "Star-Spangled Banner" occurred in 2014 with various special events occurring throughout the United States. A peculiarly pregnant celebration occurred during the week of September ten–16 in and effectually Baltimore, Maryland. Highlights included playing of a new arrangement of the canticle arranged past John Williams and participation of President Barack Obama on Defender's Solar day, September 12, 2014, at Fort McHenry.[43] In improver, the anthem bicentennial included a youth music celebration[44] including the presentation of the National Canticle Bicentennial Youth Claiming winning composition written by Noah Altshuler.

Adaptations

The first popular music operation of the anthem heard by the mainstream U.S. was by Puerto Rican singer and guitarist José Feliciano. He created a nationwide uproar when he strummed a deadening, blues-manner rendition of the song[45] at Tiger Stadium in Detroit before game five of the 1968 World Series, betwixt Detroit and St. Louis.[46] This rendition started gimmicky "Star-Spangled Banner" controversies. The response from many in the Vietnam War-era U.Due south. was by and large negative. Despite the controversy, Feliciano's performance opened the door for the countless interpretations of the "Star-Spangled Banner" heard in the years since.[47] One week afterward Feliciano's performance, the anthem was in the news once again when U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos lifted controversial raised fists at the 1968 Olympics while the "Star-Spangled Banner" played at a medal ceremony. Rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix often included a solo instrumental performance at concerts from 1968 to his expiry in 1970. Using high gain and distortion distension furnishings and the vibrato arm on his guitar, Hendrix was able to simulate the sounds of rockets and bombs at the points when the lyrics are unremarkably heard.[48] One such functioning at the Woodstock music festival in 1969 was a highlight of event'south 1970 documentary moving picture, becoming "part of the sixties Zeitgeist".[48] When asked about negative reactions to his "unorthodox" treatment of the anthem, Hendrix, who served briefly in the U.S. Ground forces, responded "I'k American so I played it... Unorthodox? I thought information technology was beautiful, only there y'all go."[49]

Marvin Gaye gave a soul-influenced operation at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game and Whitney Houston gave a soulful rendition before Super Bowl XXV in 1991, which was released as a unmarried that charted at number 20 in 1991 and number 6 in 2001 (along with José Feliciano, the but times the national anthem has been on the Billboard Hot 100).[ citation needed ] Roseanne Barr gave a controversial operation of the canticle at a San Diego Padres baseball game at Jack Murphy Stadium on July 25, 1990. The comedian belted out a screechy rendition of the vocal, and afterward, she mocked ballplayers past spitting and grabbing her crotch as if adjusting a protective cup. The performance offended some, including the sitting U.S. president, George H. W. Bush.[l] Steven Tyler also acquired some controversy in 2001 (at the Indianapolis 500, to which he later issued a public apology) and over again in 2012 (at the AFC Championship Game) with a cappella renditions of the song with changed lyrics.[51] In 2016, Aretha Franklin performed a rendition before the nationally-televised Minnesota Vikings-Detroit Lions Thanksgiving Day game lasting more iv minutes and featuring a host of improvisations. It was one of Franklin'due south final public appearances before her 2018 death.[52] Black Eyed Peas singer Fergie gave a controversial performance of the anthem in 2018. Critics likened her rendition to a jazzy "sexed-up" version of the canticle, which was considered highly inappropriate, with her performance compared to that of Marilyn Monroe's iconic performance of Happy Birthday, Mr. President. Fergie later apologized for her functioning of the vocal, stating that ''I'm a risk taker artistically, but conspicuously this rendition didn't strike the intended tone".[53]

In March 2005, a regime-sponsored plan, the National Anthem Projection, was launched after a Harris Interactive poll showed many adults knew neither the lyrics nor the history of the anthem.[54]

Lyrics

O say can you come across, by the dawn's early lite,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight'southward last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and brilliant stars through the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket'southward scarlet glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the nighttime that our flag was nonetheless there;

O say does that star-spangled imprint yet moving ridge

O'er the land of the complimentary and the home of the brave?On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe'due south haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep,

As information technology fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morn'due south first axle,

In total celebrity reflected now shines in the stream:

'Tis the star-spangled imprint, O long may it moving ridge

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave.And where is that ring who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of state of war and the battle'due south confusion,

A dwelling and a country, should get out us no more than?

Their blood has done out their foul footsteps' pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled imprint in triumph doth wave,

O'er the land of the costless and the home of the brave.O thus exist it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved homes and the war's pathos.

Blessed with vict'ry and peace, may the Heav'due north rescued state

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved u.s. a nation!

And so conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: 'In God is our trust.'

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O'er the land of the free and the habitation of the brave![55]

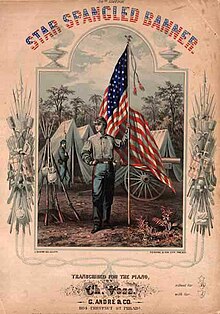

Cover of sheet music for "The Star-Spangled Banner", transcribed for pianoforte past Ch. Voss, Philadelphia: G. Andre & Co., 1862

Boosted Ceremonious War menses lyrics

Eighteen years later on Cardinal'due south death, and in indignation over the start of the American Civil War, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.[56] added a fifth stanza to the vocal in 1861, which appeared in songbooks of the era.[57]

When our land is illumined with Liberty'due south smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow at her celebrity,

Downwards, downwards with the traitor that dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page of her story!

Past the millions unchained, who our birthright have gained,

We will keep her bright blazon forever unstained!

And the Star-Spangled Imprint in triumph shall wave

While the land of the free is the home of the dauntless.

Alternative lyrics

In a version manus-written by Francis Scott Key in 1840, the third line reads: "Whose bright stars and broad stripes, through the clouds of the fight".[58] In honor of the 1986 rededication of the Statue of Liberty, Sandi Patty wrote her version of an boosted poetry to the anthem.[59]

References in picture, television, literature

Several films accept their titles taken from the song's lyrics. These include two films titled Dawn'southward Early on Calorie-free (2000[60] and 2005);[61] two fabricated-for-TV features titled By Dawn's Early Light (1990[62] and 2000);[63] 2 films titled So Proudly We Hail (1943[64] and 1990);[65] a feature film (1977)[66] and a short (2005)[67] titled Twilight's Final Gleaming; and four films titled Dwelling of the Brave (1949,[68] 1986,[69] 2004,[70] and 2006).[71] A 1936 brusque titled The Song of a Nation from Warner Bros. Pictures shows a version of the origin of the song.[72] The title of Isaac Asimov's curt story No Refuge Could Save is a reference to the vocal's tertiary verse, and the obscurity of this poetry is a major plot bespeak.[73]

Community and federal law

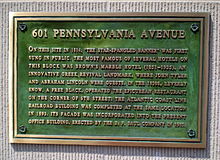

Plaque detailing how the custom of standing during the U.S. national anthem came about in Tacoma, Washington, on October xviii, 1893, in the Bostwick building

When the U.Due south. national anthem was offset recognized by law in 1931, in that location was no prescription as to beliefs during its playing. On June 22, 1942, the law was revised indicating that those in uniform should salute during its playing, while others should just stand at attending, men removing their hats. The same code also required that women should place their hands over their hearts when the flag is displayed during the playing of the national canticle, only not if the flag was not present. On Dec 23, 1942, the law was once again revised instructing men and women to stand at attending and face in the direction of the music when information technology was played. That revision also directed men and women to identify their hands over their hearts only if the flag was displayed. Those in uniform were required to salute. On July 7, 1976, the constabulary was simplified. Men and women were instructed to stand up with their hands over their hearts, men removing their hats, irrespective of whether or not the flag was displayed and those in uniform saluting. On August 12, 1998, the law was rewritten keeping the same instructions, but differentiating between "those in uniform" and "members of the Armed forces and veterans" who were both instructed to salute during the playing whether or not the flag was displayed. Because of the changes in law over the years and defoliation between instructions for the Pledge of Allegiance versus the National Anthem, throughout most of the 20th century many people simply stood at attention or with their hands folded in front of them during the playing of the Anthem, and when reciting the Pledge they would hold their hand (or hat) over their heart. After nine/11, the custom of placing the paw over the eye during the playing of the national anthem became almost universal.[74] [75] [76]

Since 1998, federal law (viz., the United States Code 36 UsaC. § 301) states that during a rendition of the national anthem, when the flag is displayed, all present including those in compatible should stand up at attending; non-military service individuals should face the flag with the correct hand over the heart; members of the Armed Forces and veterans who are present and non in uniform may render the military salute; military service persons not in uniform should remove their headdress with their correct hand and hold the headdress at the left shoulder, the hand being over the middle; and members of the Armed forces and veterans who are in uniform should give the military salute at the first note of the anthem and maintain that position until the last annotation. The law farther provides that when the flag is not displayed, all present should face up toward the music and deed in the same manner they would if the flag were displayed. Armed services law requires all vehicles on the installation to terminate when the vocal is played and all individuals exterior to stand up at attending and face the direction of the music and either salute, in uniform, or place the right hand over the heart, if out of uniform. The constabulary was amended in 2008, and since allows war machine veterans to salute out of uniform, as well.[77] [78]

The text of 36 U.S.C. § 301 is suggestive and not regulatory in nature. Failure to follow the suggestions is non a violation of the law. This behavioral requirement for the national anthem is field of study to the same Starting time Amendment controversies that surround the Pledge of Fidelity.[79] For example, Jehovah'southward Witnesses do non sing the national canticle, though they are taught that standing is an "ethical decision" that individual believers must make based on their censor.[80] [81] [82]

Translations

Every bit a consequence of clearing to the United States and the incorporation of non-English-speaking people into the country, the lyrics of the song have been translated into other languages. In 1861, it was translated into German.[83] The Library of Congress likewise has tape of a Spanish-linguistic communication version from 1919.[84] It has since been translated into Hebrew[85] and Yiddish past Jewish immigrants,[86] Latin American Castilian (with i version popularized during immigration reform protests in 2006),[87] French by Acadians of Louisiana,[88] Samoan,[89] and Irish.[90] The 3rd verse of the anthem has also been translated into Latin.[91]

With regard to the indigenous languages of Northward America, there are versions in Navajo[92] [93] [94] and Cherokee.[95]

Protests

1968 Olympics Black Power salute

The 1968 Olympics Blackness Power salute was a political demonstration conducted past African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics in the Olympic Stadium in United mexican states City. Later having won gold and bronze medals respectively in the 200-meter running event, they turned on the podium to face their flags, and to hear the American national canticle, "The Star-Spangled Banner". Each athlete raised a black-gloved fist, and kept them raised until the anthem had finished. In addition, Smith, Carlos, and Australian silver medalist Peter Norman all wore human rights badges on their jackets. In his autobiography, Silent Gesture, Smith stated that the gesture was non a "Black Power" salute, merely a "human rights salute". The event is regarded as i of the most overtly political statements in the history of the modernistic Olympic Games.[96]

Protests against police brutality (2016–present)

Protests against police brutality and racism past kneeling on one knee joint during the national anthem began in the National Football game League afterwards San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick knelt during the anthem, every bit opposed to the tradition of standing, in response to police brutality in the Usa, earlier his team's third preseason game of 2016. Kaepernick sat during the first two preseason games, but he went unnoticed.[97] In detail, protests focus on the discussion of slavery (and mercenaries) in the third verse of the anthem, in which some have interpreted the lyrics equally condemning slaves that had joined the British in an effort to earn their freedom.[98] Since Kaepernick'south protestation, other athletes take joined in the protests. In the 2017 season, after President Donald Trump's condemnation of the kneeling, which included calling for complacent players (whom he reportedly also referred to by various profanities)[ commendation needed ] to be fired, many NFL players responded by protesting during the national anthem that calendar week. After the police-involved killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, when the 2020–21 NBA season resumed play in July 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of players and coaches kneeled during the national anthem through the end of the flavour.

California affiliate of the NAACP call to remove the national canticle

In November 2017, the California Chapter of the NAACP called on Congress to remove "The Star-Spangled Imprint" every bit the national anthem. Alice Huffman, California NAACP president, said: "It's racist; it doesn't stand for our customs, it's anti-black."[99] The tertiary stanza of the anthem, which is rarely sung and few know, contains the words "No refuge could relieve the hireling and slave, from the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave", which some interpret as racist. The system was still seeking a representative to sponsor the legislation in Congress at the time of its announcement.[ citation needed ]

Media

See also

- In God We Trust

- "God Bless America"

References

- ^ a b ""Star-Spangled Imprint" Is At present Official Anthem". The Washington Post. March 5, 1931. p. three.

- ^ "Defence of Fort M'Henry | Library of Congress". Loc.gov . Retrieved April xviii, 2017.

- ^ "My state 'tis of thee [Song Collection]". The Library of Congress. Retrieved January twenty, 2009.

- ^ Snyder, Lois Leo (1990). Encyclopedia of Nationalism . Paragon Firm. p. 13. ISBN1-55778-167-2.

- ^ Estrella, Espie (September 2, 2018). "Who Wrote "America the Cute"? The History of America's Unofficial National Anthem". thoughtco.com. ThoughtCo. Retrieved November fourteen, 2018.

Many consider "America the Cute" to exist the unofficial national anthem of the United States. In fact, it was one of the songs beingness considered as a U.S. national canticle before "Star Spangled Banner" was officially chosen.

- ^ British Rockets at the US National Park Service, Fort McHenry National Monument, and Historic Shrine. Retrieved February 2008. Archived April 3, 2014, at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ "John Wiley & Sons: 200 Years of Publishing – Birth of the New American Literature: 1807–1826". Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Defence of Fort Yard'Henry". The Analectic Magazine. 4: 433–434. Nov 1814. hdl:2027/umn.31951000925404p.

- ^ "When the Warrior Returns – Key". Potw.org . Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Vile, John R. (2021). America's National Anthem: "The Star-Spangled Banner" in U.Southward. History, Culture, and Law. ABC-CLIO. p. 277. ISBN978-1-4408-7319-five.

Central equanimous a poem for an event honoring Stephen Decatur and Charles Stewart, two heroes of the war in Tripoli

- ^ Blackburn, Robin (1988). The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848. pp. 288–290.

- ^ a b c Mark Clague (August 31, 2016). "'Star-Spangled Banner' critics miss the signal". CNN.com . Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "Colin Kaepernick Is Righter Than You Know: The National Canticle Is a Celebration of Slavery". Theintercept.com. August 28, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "Is the National Anthem Racist? Beyond the Debate Over Colin Kaepernick". The New York Times. September 3, 2016. Archived from the original on November ii, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "'The Star-Spangled Imprint' and Slavery". Snopes.com . Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Clague, Marker, and Jamie Vander Broek. "Banner moments: the national canticle in American life". Academy of Michigan, 2014. 4.

- ^ "Oratorio Guild of New York – Star Spangled Imprint". Oratoriosocietyofny.org. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved Apr xviii, 2017.

- ^ "Standardization Manuscript for "The Star Spangled Banner" | Antiques Roadshow". PBS. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Plaque, Fort Meade, erected 1976 by the Fort Meade V.A. Hospital and the Due south Dakota Land Historical Society

- ^ a b Cavanaugh, Ray (July four, 2016). "The Star-Spangled Banner: an American anthem with a very British outset". The Guardian . Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- ^ "Cubs vs Ruby Sox 1918 World Series: A Tradition is Born". Baseballisms.com. May 21, 2011. Retrieved April xviii, 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as championship (link) - ^ a b c "National Anthem Hearing Is Set For January 31". The Baltimore Sunday. Jan 23, 1930. p. iv.

- ^ "Company News – Ripley Entertainment Inc". Ripleysnewsroom.com . Retrieved Apr eighteen, 2017.

- ^ a b "v,000,000 Sign for Anthem: Fifty-Mile Petition Supports "The Star-Spangled Banner" Bill". The New York Times. January 19, 1930. p. 31.

- ^ "five,000,000 Plea For U.S. Anthem: Giant Petition to Exist Given Judiciary Committee of Senate Today". The Washington Mail. Jan 31, 1930. p. 2.

- ^ "Commission Hears Star-Spangled Banner Sung: Studies Bill to Get in the National Anthem". The New York Times. February 1, 1930. p. ane.

- ^ "'Star-Spangled Banner' Favored Equally Anthem in Written report to House". The New York Times. February 5, 1930. p. 3.

- ^ a b "'Star Spangled Banner' Is Voted National Canticle by Congress". The New York Times. March iv, 1931. p. ane.

- ^ 36 U.S.C. § 301.

- ^ Fisher, Louis; Mourtada-Sabbah, Nada (2002). "Adopting In God We Trust as the U.Southward. National Motto". Periodical of Church and State. 44 (4): 682–83. doi:10.1093/jcs/44.4.671 – via HeinOnline.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) (Referencing H. Rept. No. 1959, 84th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1956) and South. Rept. No. 2703, 84th Cong., second Sess. (1956), two.) - ^ Theroux, Alexander (Feb 16, 2013). The Grammer of Stone: Art and Candor in 20th Century Pop Lyrics. Fantagraphics Books. p. 22. ISBN9781606996164.

- ^ "Aguilera flubs national canticle at Super Bowl". CNN. February 6, 2011.

- ^ "The Fenway Project – Part One". Red Sox Connection. May 2004. Archived from the original on January ane, 2016.

- ^ "History.com article para half-dozen". History.com. September 25, 2017. Archived from the original on September sixteen, 2018.

- ^ Allen, Kevin (March 23, 2003). "NHL Seeks to Stop Booing For a Song". USA Today . Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- ^ "Fanzone, A–Z Guide: National Anthems". Buffalo Sabres . Retrieved Nov 20, 2014.

If you lot are interested in singing the National Anthems at a sporting issue at First Niagara Eye, yous must submit a DVD or CD of your performance of both the Canadian & American National Anthems...

- ^ Graves, David (September 14, 2001) "Palace breaks with tradition in musical tribute". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved August 24, 2011

- ^ Steyn, Mark (September 17, 2001). "The Queen'due south Tears/And global resolve against terrorism". National Review. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved April ten, 2013.

- ^ "Hong Kong protesters sing U.S. canticle in appeal for Trump'due south help". NBC News. Archived from the original on September 10, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ McLaughlin, Timothy; Quackenbush, Casey. "Hong Kong protesters sing 'Star-Spangled Banner,' phone call on Trump to 'liberate' the city". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Cherney, Mike (October 14, 2019). "Thousands Rally in Hong Kong for U.South. Bill Supporting City's Autonomy". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Michael E. Ruane (September 11, 2014). "Francis Scott Key's anthem keeps asking: Have we survived as a nation?". The Washington Postal service.

- ^ [1] Archived November 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 52 – The Soul Reformation: Phase three, soul music at the tiptop. [Part 8]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Academy of North Texas Libraries. Track 5.

- ^ Paul White, United states Today Sports (October 14, 2012). "Jose Feliciano's once-controversial anthem kicks off NLCS". Usatoday.com. Retrieved November ix, 2013.

- ^ Jose Feliciano Personal account almost the anthem performance Archived October eight, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Cantankerous, Charles R. (2005). Room Full of Mirrors: A Biography of Jimi Hendrix (1st. Merchandise Paperback ed.). New York City: Hyperion Books. pp. 271–272. ISBN0-7868-8841-5.

- ^ Roby, Steven (2012). Hendrix on Hendrix: Interviews and Encounters with Jimi Hendrix. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN978-1-61374-322-five.

- ^ Letofsky, Irv (July 28, 1990). "Roseanne Is Sorry – but Not That Sorry". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved September fourteen, 2012.

- ^ "AOL Radio – Heed to Free Online Radio – Free Net Radio Stations and Music Playlists". Spinner.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ "That time Aretha Franklin dazzled America on Thanksgiving with national anthem". WJBK. August 13, 2018. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Fergie apologises for national anthem". BBC News. February 20, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ "Harris Interactive poll on "The Star-Spangled Banner"". Tnap.org. Archived from the original on Jan 12, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ Francis Scott Central, The Star Spangled Banner (lyrics), 1814, MENC: The National Association for Music Education National Anthem Project (archived from the original Archived Jan 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine on 2013-01-26).

- ^ Butterworth, Hezekiah; Brown, Theron (1906). "The Story of the Hymns and Tunes". George H. Doran Co.: 335.

- ^ The soldier'due south companion: dedicated ... 1865. Retrieved June 14, 2010 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Library of Congress image". Library of Congress . Retrieved June fourteen, 2010.

- ^ Bream, Jon (September 25, 1986). "Televised Anthem Brings Sandi Patty Liberty." Archived August 3, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune (ChicagoTribune.com). Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ Dawn'south Early Light (2000) on the Internet Moving picture Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Dawn's Early Light (2005) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September xiv, 2007.

- ^ Dawn'due south Early Light TV (1990) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Dawn'southward Early Lite TV (2000) on the Net Picture Database. Retrieved September fourteen, 2007.

- ^ So Proudly We Hail (1943) on the Net Motion picture Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ So Proudly We Hail (1990) on the Net Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977) on the Net Film Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Twilight's Last Gleaming (2005) on the Cyberspace Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Dwelling of the Brave (1949) on the Internet Flick Database. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ Dwelling of the Dauntless (1986) on the Cyberspace Movie Database. Retrieved December v, 2007.

- ^ Home of the Brave (2004) on the Net Movie Database. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ Home of the Brave (2006) on the Net Motion picture Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ [ii],

- ^ "Tricks on How to Spot a Spy". SOFREP. May seven, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ "Public Laws, June 22, 1942". June 22, 1942.

- ^ "77th Congress, 2nd session". uscode.house.gov . Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ "Public police, July 7, 1976". uscode.house.gov . Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ Duane Streufert. "A website dedicated to the Flag of the United States of America – United states Code". USFlag.org. Retrieved June fourteen, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. Code". Uscode.house.gov. Archived from the original on May 29, 2012. Retrieved June xiv, 2010.

- ^ The Circle School v. Phillips, 270 F. Supp. 2d 616, 622 (East.D. Pa. 2003).

- ^ "Highlights of the Beliefs of Jehovah'southward Witnesses". Towerwatch.com. Archived from the original on September xviii, 2009. Retrieved June fourteen, 2010.

- ^ Botting, Gary Norman Arthur (1993). Fundamental freedoms and Jehovah'south Witnesses. University of Calgary Press. p. 27. ISBN978-one-895176-06-3 . Retrieved Dec thirteen, 2009.

- ^ Chryssides, George D. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Jehovah'due south Witnesses. Scarecrow Press. p. 34. ISBN978-0-8108-6074-two . Retrieved Jan 24, 2014.

- ^ Das Star-Spangled Banner, United states Library of Congress. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ La Bandera de las Estrellas, U.s.a. Library of Congress. Retrieved May 31, 2005.

- ^ Hebrew Version

- ^ Abraham Asen, The Star Spangled Banner in pool, 1745, Joe Fishstein Drove of Yiddish Poetry, McGill University Digital Collections Program. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Day to Day. "A Spanish Version of 'The Star-Spangled Banner'". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ David Émile Marcantel, La Bannière Étoilée Archived May 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine on Musique Acadienne. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Zimmer, Benjamin (April 29, 2006). "The Samoa News reporting of a Samoan version". Itre.cis.upenn.edu. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ "An Bhratach Gheal-Réaltach – Irish version". Daltai.com. Archived from the original on Dec 10, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ Christopher M. Brunelle, Third Poetry in Latin, 1999

- ^ "Gallup Independent, 25 March 2005". Gallupindependent.com. March 25, 2005. Archived from the original on Feb 3, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ [3] [ dead link ]

- ^ "Schedule for the Presidential Inauguration 2007, Navajo Nation Regime". Navajo.org. January 9, 2007. Archived from the original on December two, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ "Cherokee Phoenix, Accessed 2009-08-15". Cherokeephoenix.org. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Richard (October eight, 2006). "Caught in Time: Blackness Ability salute, Mexico, 1968". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved Nov ix, 2008.

- ^ Sandritter, Marker (September 11, 2016). "A timeline of Colin Kaepernick'due south national canticle protest and the NFL players who joined him". SB Nation. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- ^ Woolf, Christopher (August 30, 2016). "Historians disagree on whether 'The Star-Spangled Banner' is racist". The World. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ "National anthem lyrics prompt California NAACP to call for replacing vocal". Retrieved Nov 8, 2017.

Further reading

- Christgau, Robert (Baronial thirteen, 2019). "Jimi Hendrix's 'Star-Spangled Banner' is the anthem we need in the age of Trump". Los Angeles Times.

- Ferris, Marc. Star-Spangled Banner: The Unlikely Story of America's National Canticle. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. ISBN 9781421415185 OCLC 879370575

- Leepson, Marc. What Then Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, a Life. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. ISBN 9781137278289 OCLC 860395373

- Poems of the late Francis South. Key, esq., writer of "The Star Spangled Banner" ; with an introductory alphabetic character by Chief Justice Taney , Published 1857 (The letter from Chief Justice Taney tells u.s. the history backside the writing of the poem written by Francis Scott Primal),[1]

External links

- "New volume reveals the dark history backside the Star Spangled Banner", CBS This Morning, September thirteen, 2014 (via YouTube).

- "Star-Spangled History: five Facts About the Making of the National Anthem", Biography.com.

- "'Star-Spangled Imprint' writer had a complex record on race", Mary Carole McCauley, The Baltimore Sun, July 26, 2014.

- "The Human being Backside the National Anthem Paid Piddling Attention to It". NPR's Here and Now, July 4, 2017.

- Star-Spangled Banner (Retention)—American Treasures of the Library of Congress exhibition

- "How the National Canticle Has Unfurled; 'The Star-Spangled Imprint' Has Changed a Lot in 200 Years" by William Robin. June 27, 2014, The New York Times, p. AR10.

- Telly bout of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History Star-Spangled Banner exhibit—C-Bridge, American History, May 15, 2014

Historical audio

- "The Star Spangled Banner", The Diamond Four, 1898

- "The Star Spangled Banner", Margaret Woodrow Wilson, 1915

- ^ Key, Francis Scott (Apr 24, 1857). "Poems of the late Francis S. Key, Esq., writer of "The Star spangled banner" : with and introductory letter by Chief Justice Taney". New York : Robert Carter & Brothers – via Cyberspace Annal.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Star-Spangled_Banner

Posted by: lopezthapt1997.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Us Senator Wants To Change Our National Anthem"

Post a Comment