What The Bible Says About Climate Change

The beginning fourth dimension I interviewed Matt Humphrey, we were driving in his pickup truck through southern British Columbia, passing fields and forests, only three miles from the U.S. border. Humphrey, then 31 years onetime, is a father of three and an evangelical Christian with a cracking appreciation for the Bible. He is besides an environmentalist, one who believes fighting climate change is a moral duty.

On the 18-acre belongings nosotros were heading to, Humphrey and others from an evangelical Christian group called A Rocha (pronounced a-RAH-shah) were growing organic crops, running Bible workshops, and helping young people get out in nature to study species like salmon in a river that flowed through their land. It's chosen the Brooksdale Environmental Heart, and Humphrey, 6-foot-3 with a broad smile, was its assistant director at the time. I've been in touch with Humphrey for a few years, and information technology was on our bulldoze to Brooksdale that he starting time described his faith to me — and how information technology shaped his environmentalism.

"I don't want to merits that Christianity gives the best understanding of the surroundings," he said, "only for those who are claiming to be Christian, part of that discipleship involves a relationship with creation."

Spend time with Christian environmentalists and you'll hear the word "cosmos" a lot. It refers to the biblical story of Genesis, in which God created the globe in 7 days, forming the oceans and forests, plants and animals, before crafting the first humans. Evangelical Christians have the Bible more literally than nigh; even so they oasis't always been as serious nigh protecting what God made. Growing ranks of younger evangelicals, however, forth with members of organizations like A Rocha, see themselves more as stewards, grounding their concern for nature and the planet in the Bible. They view their environmentalism as caring for cosmos. If God fabricated the planet and all that'south in it, the reasoning goes, shouldn't pains exist taken to protect it?

For nigh American evangelicals, the answer is far from clear. Effectually a quarter of Americans — 84 one thousand thousand — call themselves evangelical Christians. Co-ordinate to the Pew Inquiry Heart, a majority lean Republican and don't buy the science backside homo-made climate change. White evangelicals in particular are amid the least probable to accept the science: Simply 28 per centum believe humans crusade global warming. This has vast implications for politics as well as getting policies in identify to tackle the growing crisis. Some 81 percent of white evangelicals in 2016 voted for Donald Trump, who then spent iv years in the White Firm trying to tear down a one-half-century of environmental protections. In last yr's election, 75 percent of them wanted to give him another four years.

Humphrey grew up in Virginia'south Shenandoah Valley and moved to the coast to study at Christopher Newport University, a public, secular college in Newport News that drew many evangelical Christians from the region. "I went to college during the [George Due west.] Bush years," he said, "when to be a Christian oft meant having an American flag decal on your car." Humphrey understood the evangelicals who doubted established scientific discipline better than most, but when nosotros caught upwardly recently, he told me even he didn't see 2016 coming. "I was frankly surprised by the success of Trump," he said. Some friends back home expressed skepticism over his interest with A Rocha and environmental issues. Ane told him that environmental groups were function of a sinister plot, led by Al Gore, to seize power.

Many younger evangelicals, however, are open up to new ideas and appear to accept the scientific evidence. 1 Pew study found a bulk of evangelical millennials support stricter ecology laws, and groups like Young Evangelicals for Climate Action are leading the charge.

Humphrey has straddled these two worlds — correct-wing politics and evangelical environmentalism — and information technology provides him with a unique perspective, as well as a potential bridge. He's office of a group of evangelicals who, with their embrace of mainstream science, conservation, and ecology protections, don't fit the bourgeois stereotype.

The definition of "evangelical" Christian isn't always articulate-cutting. In popular usage, it includes Protestants who accept the Bible very seriously, as much more a drove of parables and ancient history. But it may also cover those who emphasize the redemption of Jesus's crucifixion, believe non-Christians demand to be converted, and that faith shouldn't be divorced from politics.

I thing many American evangelicals share is a skepticism of climate scientific discipline for reasons that include theology, politics, and a hostility to the theory of evolution. Darwin's theory, of grade, suggested that humans evolved over millennia through natural selection and shared ancestors with modern apes, an idea which tin can't be easily squared with a conventionalities that the Volume of Genesis is a fact-based origin story.

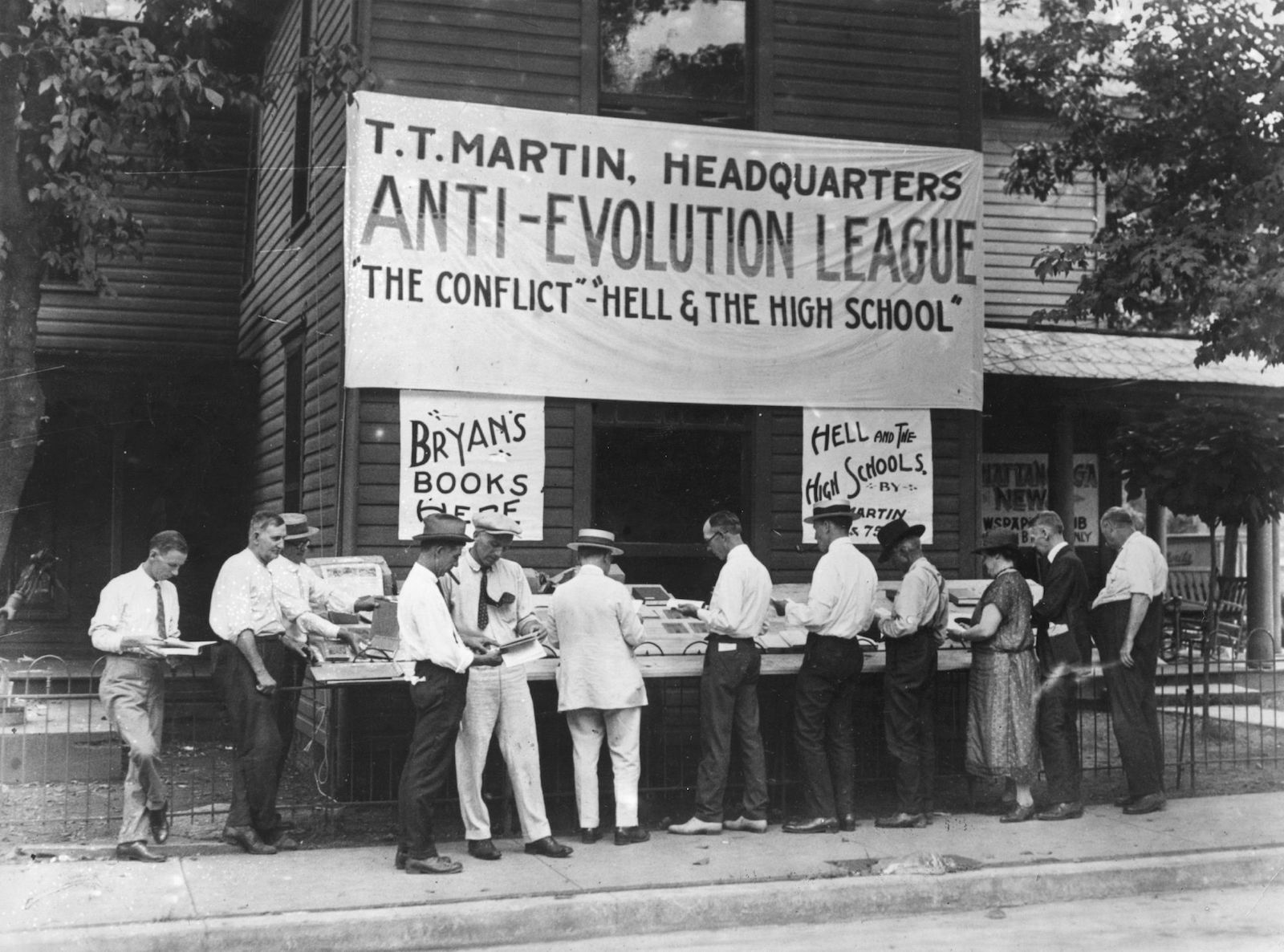

In 1925, the Scopes "Monkey" Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, pitted a loftier-school instructor and football game coach, John Thomas Scopes, confronting the state, which had a law on the books that prohibited him from teaching development. The media coverage of the case bandage fundamentalist Christians as backward and anti-intellectual. The jury found Scopes guilty, but evangelicals lost in the court of public opinion: The stigma stuck, and many grew even more skeptical of science and scientists.

While Darwinism helps explain some American evangelicals' aversion to science, it's politics that best explains their disfavor to climate science. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan promoted evangelical views in substitution for votes. In doing so, a decades-long alliance was formed. Equally prove accumulated that humans were heating up the planet, that relationship meant evangelicals were in lockstep with Republicans when climate alter became a charged partisan outcome. In the early 2000s, a leading GOP strategist, Frank Luntz, wrote a at present infamous memo advising the party and and so-President George W. Bush to button the line that the consensus effectually climatic change was still up for debate. "Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled," he wrote, "their views about global warming volition change appropriately. Therefore, you lot need to proceed to brand the lack of scientific certainty a primary consequence." For many evangelicals, a hostility to climate science became a bluecoat of identity. (Luntz, however, would afterwards make an near-face.)

How strong are these political influences? For a large segment of evangelicals, "their statement of faith is written primarily by their politics, and only secondarily by their faith," said Katharine Hayhoe, the prominent climate scientist and herself an evangelical Christian, who was named one of Time Magazine'southward most influential people for her piece of work bridging divides. "If the two come in conflict, they will go with their politics over what they merits to believe."

Merely there remains a large segment of "theological evangelicals," she told me, "whose argument of faith is written past the Bible." Those are the people Humphrey wants to accomplish.

In 1967, the historian Lynn White Jr. published a brusk essay in the journal Science. "The Historical Roots of our Ecological Crunch" argued that the Christian worldview could be blamed for the rapid footstep of ecology destruction. White wrote that the biblical story of creation gave Christians an impetus to dominate the state. Genesis, after all, called on people to "subdue" the Earth and to have "rule over the fish of the ocean, and over the birds of the air." It was God'southward will. White wrote that this dogma entrenched the thought that the natural globe served no purpose "save to serve man'southward purposes," which influenced the evolution of modern applied science and the ecological crisis it wrought.

White already saw climate change as a event of this worldview. "Our present combustion of fossil fuels threatens to alter the chemical science of the globe'due south atmosphere equally a whole, with consequences which we are simply beginning to gauge," he wrote.

The essay set off a debate that still burns today. Reams of papers were written for and confronting, it remains a staple on university reading lists, and information technology helped shape the field of environmental ethics. The essay also prompted soul-searching amidst some Christians, leading them to ask how they could embrace the growing environmental motility. "It really is amazing how influential these five pages from the periodical of Science were," Humphrey said, "and I think that's because many of White's arguments struck a chord."

Over the next half-century, many Christians imbued their religion with a business organization for the natural world. To counter the thought of "dominion," they went dorsum to the book of Genesis. The aforementioned story, they said, asked people to "work and take care of" the land, and to "let the birds increase on the world." Rather than interpreting the story of cosmos equally a license to boss, these Christians consider it a telephone call to protect and steward the landscape.

A Rocha was founded in Portugal by two British evangelicals, Peter and Miranda Harris, in the 1980s. (A Rocha means "the rock" in Portuguese.) About the estuary of the Ria de Alvor on the southern coast, dwelling house to 150 bird species, the Harrises collected data, conducted research, and protected a variety of birds. Today the organization they started has projects in more than than 20 countries, including the United states, Lebanese republic, Uganda, and Peru.

In his 2008 volume Kingfisher's Burn down, Peter Harris laid out the connection betwixt his religion and the organization'south conservation efforts, an caption rooted in both scientific discipline and caring for God'due south creation. "We believe our information can contribute to the survival of the habitats and species we are studying," he wrote. "Our work for the care of nonhuman creation is important to its Creator." A Rocha's moderate evangelical culture also stems, in part, from its British roots, where the temper is less politically charged compared to the United States.

Hayhoe, who has spoken at A Rocha'south events and acted every bit an advisor to the organization, thinks the Bible makes this responsibility clear. "If we really take the Bible seriously, we would be at the front of the line demanding climate activeness," she said. "For somebody who is, at to the lowest degree, even partially a theological evangelical, who actually takes the Bible seriously, that is a huge indicate of connexion."

Over the years, Humphrey's own environmental awareness increased through his work as a guide in British Columbia's Coast Mountains, and by reading stories of ecological destruction in magazines like Orion and Female parent Jones. Theology and the Bible also later shaped his ecology worldview. And ane mean solar day, non far from the Brooksdale Ecology Heart, I visited the Columbia Bible College in Abbotsford to watch Humphrey give a presentation on what's known as ecotheology.

In front of students in their teens and 20s, Humphrey tried to provide what he rarely had when he was younger: a biblical perspective, free from partisan politics, that embraced the scientific consensus around climatic change and other ecology issues. The room was packed, and I turned to a immature couple behind me, Glenn and Katie, to chat. For two people at a weekend talk on ecotheology, they were pretty skeptical nigh the subject. "I wouldn't want my faith to enter my activism, because I'm aback of the damage Christianity has caused over the centuries," Katie said.

Humphrey also harbors his share of doubts. He would be the first to tell y'all that people have used the Bible to justify horrible acts. But he besides thinks that Christians shouldn't be bystanders to modern ecological calamities, and that the Bible might be used to inspire Christians to care for God'due south cosmos. To illustrate this, he told the students about the story of Naboth's vineyard.

In the Book of Kings, a human being named Naboth was pressured past a wealthy king, Ahab, to sell his state. Naboth refused because the soil provided food for his family unit, and the land was an inheritance from his ancestors. Ahab's wife, Jezebel, so set up up an elaborate ruse which wound up with Naboth being executed and Male monarch Ahab getting the vineyard.

Humphrey described this story as a struggle between a defiant farmer and a military ruler, and he believed this theme of resistance echoed through other biblical stories in which agrarian people, in tune with the land and the seasons, often had to fight powerful Ahabs to protect what they had. He then drew a parallel to modern times, describing how, around the world, land and natural resource are often degraded and commodified by powerful people who put profit earlier the needs of local communities. "Nosotros therefore demand, now more than than always, to recover the deep sense of our membership within, and dependence upon, cosmos," Humphrey said. "And nosotros need to put this into practice with concrete social and ecological action."

Later on he finished, the room buzzed with churr, and I turned back to Glenn and Katie to get their reaction. This time Glenn chimed in: "You don't frequently hear it said in this fashion, or with a call to action similar that." Similar to Katie, though, he was hesitant about mixing theology with ecology activism, and wondered if pointing to Bible passages for support was the best idea.

"It'due south encouraging to know that in that location are parts of the tradition that can exist helpfully appropriated, but y'all can't pigment the whole Bible with the same brush," Glenn said. "I think some parts of the Bible are downright problematic. For example, Naboth'south vineyard is an crawly challenge to power, just there are many other instances where people accede to power."

Some, similar Katie and Glenn, might be wary of involving organized religion in ecology discussions. After all, Christianity and Islam famously battled with science, and deeply religious civilizations destroyed their natural environments. All the same the reality is that religions however shape how a majority of people view the world. Muslims, Christians, and Hindus together stand for five.two billion people, or two-thirds of the world'due south population.

For evangelicals concerned about climate change, questions of morality seem to counterbalance as heavily every bit those of science. Humphrey doesn't only care about nature or creation — the scorched forests and the melting polar ice caps — but too about the human fallout from climate change in the decades ahead: Rise seas destroying the homes of millions around the world, devastating droughts causing millions more than to go hungry. He oft worries nigh how people volition respond when confronted with this version of the hereafter.

"What sort of people will we be if the CO2 in the temper isn't easy to set up? What sort of people will we be if things go hard, like scary hard?" Humphrey asked me. "What will hold us capable of living lives of justice and honey and goodness for the vulnerable, once the illusion of safe and affluence slips?"

Humphrey, at least, thinks the Christian church can help answer these moral questions. For others, it could be Islam, Judaism, or another faith. Every bit climate change inflames divisions in order, people like Humphrey believe the response requires not just solar power, electric cars, and mass transit, just too teachings of love, prayer, and forgiveness.

It was in this spirit that more than than seventy Christian leaders, climate scientists, and government officials gathered in 2002 at the University of Oxford to discuss the threat of global warming and how to reconcile their response with Christian imperatives, as Katharine Wilkinson described in her book, Between God and Light-green. Drawing on both science and ecotheology, they produced the "Oxford Declaration on Global Warming." It urged Christians to face up climate alter, for scientific reasons equally well as moral ones. After all, the effects of climate change, like severe drought, storms, and rising ocean levels, disproportionately hurt the world's poor. To "love thy neighbour every bit thyself," they reasoned, should likewise hateful to help them.

This shift in thinking and growing public concern for the environment opened the style for the Evangelical Climate Initiative and its 2006 "Call to Action." Similar to the Oxford Declaration simply with a focus on evangelicals, the "Phone call to Action" brought formerly reluctant evangelical leaders together over climatic change. The statement acknowledged that they took a while to accept the seriousness of the crisis, just ultimately they were "convinced that evangelicals must engage this event."

Megachurch pastors with tens of thousands of followers, like Joel Hunter and Rick Warren, pastor of Saddleback Church, soon signed on. This evangelical motion has faced a backlash from many congregations across the country, and information technology hasn't broken the connection betwixt climate-denying Republicans and well-nigh evangelicals, but new ways of thinking have taken root.

With an audition of billions, pastors like Hunter and Warren, along with priests, imams, and rabbis, could be powerful advocates for climate activeness. In a 2016 essay, two religious scholars at Yale University, Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, considered the role of religious leaders in spurring social change over recent decades, whether in movements for civil rights or in advocating for the poor. "Although the world religions accept been slow to answer to our electric current environmental crises, their moral authorization and their institutional power may help effect a change in attitudes, practices, and public policies." they wrote. Tucker and Grim, a married couple who founded the Forum on Faith and Ecology at Yale, and so issued a challenge: "The private religions must explain and transform themselves if they are willing to enter into this period of environmental engagement." They concluded that, if this is washed, religions could "empower humans to comprehend values that sustain life and contribute to a vibrant Earth community."

Office of this engagement, Hayhoe argues, involves nurturing a sense of hope. In 2017, the American Psychological Association outset divers the term "eco-anxiety" as a "chronic fear of environmental doom," and it'southward on the rising. In a survey of British schoolchildren final year, one in v reported having nightmares about climate change. Many tin can chronicle: Simply staring at charts of rise global temperatures tin engender a sense of dread. In her 2018 TED talk, viewed 4 million times, Hayhoe described the consequences of giving in to despair, a gloom that leaves people paralyzed. "Fear is not what is going to motivate usa for the long-term, sustained change that we need to fix this thing," she said.

When I talked to her, Hayhoe was determined that nurturing hope tin be as simple every bit getting out and doing something. "Nosotros know that what gives us promise is activity, whether it's seeing others act, hearing virtually others interim, or acting ourselves."

Humphrey, for instance, has continued working with A Rocha, focusing on theological instruction, but he has also, along the fashion, go an ordained government minister. He now lives and preaches in Victoria, British Columbia, and with a group of friends, he founded the Wild Church building Victoria. On weekends, members hike local mountains, through grasses and Garry oak forests; or they visit nearby beaches and walk along pebbled shores. Exterior in nature, surrounded by cosmos, they read scripture and practice their eco-conscious organized religion.

Information technology was at Brooksdale where I saw A Rocha's efforts to put creation care into exercise. Along the Little Campbell River, which runs through the belongings, the Salish Sucker, a pocket-sized, freshwater fish one time thought locally extinct, was rediscovered cheers to A Rocha's watershed monitoring. This alloy of science, conservation, and Christian faith seemed so at odds with the pop conception of anti-environment evangelicals.

"A Rocha beautifully embodies how we tin can care nigh people and places in a way that genuinely reflects God'south love," Hayhoe told me. "I think that genuine reflection of beloved is what attracts people to them."

Dorsum when I starting time spent time with Humphrey, riding in his truck through forests near the U.Due south. border, he drove u.s. to a lumber yard to buy slabs of wood for an outdoor shelter. When we returned to the Brooksdale farm, the cedar planks jutting from the back of the truck, the belongings'due south large garden and grassy fields came into view, ringed by a forest of alpine conifers and a gentle, meandering river.

Perhaps this proximity to nature, along with the feel of growing food and protecting wild species, helps raise awareness about the threat of climate modify and the devastation of the natural world. This is inappreciably a novel idea, as a growing body of testify shows that connexion with nature is linked to a desire to protect it. But in an era when our eyes are glued to the mini-computers in the palms of our hands, contact with nature, a fact of life for millennia, can seem radical.

For the next couple of hours at Brooksdale, I stuck around to assist build the shelter for their outdoor oven. The sound of a radial saw slicing through beams of wood filled the air. We were presently drilling nails into rafters and attaching them to boards that ran along the shelter'due south peak. By the fifth or sixth board, nosotros had the hang of it, and vicious into a routine of eye contact, head nods, and reassurances of "practiced enough."

Humphrey told me that A Rocha didn't take a church building. But information technology seemed to me that here, at Brooksdale, the volunteers were constructing a place of significance surrounded by nature: a large wooden shelter around an oven hearth, where food grown in the fields would be cooked, in acknowledgment of Earth's wonder, the fish and the birds. What they call cosmos.

Source: https://grist.org/politics/evangelical-christians-climate-action-god-mandate-bible/

Posted by: lopezthapt1997.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What The Bible Says About Climate Change"

Post a Comment